Composers

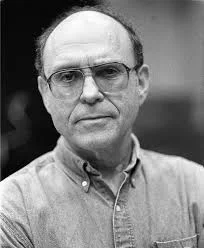

Samuel Adler

Samuel Adler (b. 1928)

Samuel Adler was born March 4, 1928, Mannheim, Germany and came to the United States in 1939. He was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters in May 2001, and then inducted into the American Classical Music Hall of Fame in October 2008. He is the composer of over 400 published works, including 5 operas, 6 symphonies, 12 concerti, 9 string quartets, 5 oratorios and many other orchestral, band, chamber and choral works and songs, which have been performed all over the world. He is the author of three books, Choral Conducting (Holt Reinhart and Winston 1971, second edition Schirmer Books 1985), Sight Singing (W.W. Norton 1979, 1997), and The Study of Orchestration (W.W. Norton 1982, 1989, 2001). He has also contributed numerous articles to major magazines and books published in the U.S. and abroad.

Adler was educated at Boston University and Harvard University, and holds honorary doctorates from Southern Methodist University, Wake Forest University, St. Mary’s Notre-Dame and the St. Louis Conservatory. His major teachers were: in composition, Herbert Fromm, Walter Piston, Randall Thompson, Paul Hindemith and Aaron Copland; in conducting, Serge Koussevitzky.

He is Professor-emeritus at the Eastman School of Music where he taught from 1966 to 1995 and served as chair of the composition department from 1974 until his retirement. Before going to Eastman, Adler served as professor of composition at the University of North Texas (1957-1977), Music Director at Temple Emanu-El in Dallas, Texas (1953-1966), and instructor of Fine Arts at the Hockaday School in Dallas, Texas (1955-1966). From 1954 to 1958 he was music director of the Dallas Lyric Theater and the Dallas Chorale. Since 1997 he has been a member of the composition faculty at the Juilliard School of Music in New York City, and was awarded the 2009-10 William Schuman Scholars Chair. Adler has given master classes and workshops at over 300 universities worldwide, and in the summers has taught at major music festivals such as Tanglewood, Aspen, Brevard, Bowdoin, as well as others in France, Germany, Israel, Spain, Austria, Poland, South America and Korea.

Some recent commissions have been from the Cleveland Orchestra (Cello Concerto), the National Symphony (Piano Concerto No. 1), the Dallas Symphony (Lux Perpetua), the Pittsburgh Symphony (Viola Concerto), the Houston Symphony (Horn Concerto), the Barlow Foundation/Atlanta Symphony (Choose Life), the American Brass Quintet, the Wolf Trap Foundation, the Berlin-Bochum Brass Ensemble, the Ying Quartet and the American String Quartet to name only a few. His works have been performed lately by the St. Louis Symphony, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra and the Mannheim Nationaltheater Orchestra. Besides these commissions and performances, previous commissions have been received from the National Endowment for the Arts (1975, 1978, 1980 and 1982), the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations, the Koussevitzky Foundation, the City of Jerusalem, the Welsh Arts Council and many others.

Adler has been awarded many prizes including a 1990 award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the Charles Ives Award, the Lillian Fairchild Award, the MTNA Award for Composer of the Year (1988-1989), and a Special Citation by the American Foundation of Music Clubs (2001). In 1983 he won the Deems Taylor Award for his book, The Study of Orchestration. In 1988-1989 he was designated “Phi Beta Kappa Scholar.” In 1989 he received the Eastman School’s Eisenhard Award for Distinguished Teaching. In 1991 he was honored being named the Composer of the Year by the American Guild of Organists. Adler was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship (1975-1976); he has been a MacDowell Fellow for five years and; during his second trip to Chile, he was elected to the Chilean Academy of Fine Arts (1993) “for his outstanding contribution to the world of music as a composer.” In 1999, he was elected to the Akademie der Künste in Germany for distinguished service to music. While serving in the United States Army (1950-1952), Adler founded and conducted the Seventh Army Symphony Orchestra and, because of the Orchestra’s great psychological and musical impact on European culture, was awarded a special Army citation for distinguished service. In May, 2003, he was presented with the Aaron Copland Award by ASCAP, for Lifetime Achievement in Music (Composition and Teaching).

Adler has appeared as conductor with many major symphony orchestras, both in the U.S. and abroad. His compositions are published by Theodore Presser Company, Oxford University Press, G. Schirmer, Carl Fischer, E.C. Schirmer, Peters Edition, Ludwig-Kalmus Music Masters, Southern Music Publishers, Transcontinental Music Publishers, and Leupold Music. Recordings of his works have been done on Naxos, RCA, Gasparo, Albany, CRI, Crystal and Vanguard.

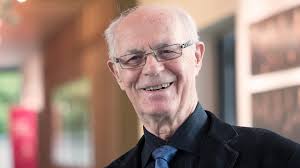

Tzvi Avni

Tzvi Avni is one of the foremost composers of Israel today. He was born in Saarbrücken, Germany, in 1927, and came to Israel as a child. Initially self-taught he continued his studies with Abel Ehrlich and Paul Ben-Haim. In 1958 he graduated from the Israel Music Academy in Tel Aviv under Mordecai Seter and later furthered his studies in the U.S.A. at the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center with Vladimir Ussachevsky and in Tanglewood with Aaron Copland and Lukas Foss. Since 1971 he has been teaching at the Jerusalem Rubin Academy of Music and Dance where he holds the position of Professor of theory and composition and served as head of the Electronic Music Studio.

His works include several orchestral pieces, chamber music for various combinations, vocal and choral music, several electronic works, as well as music for ballet, theater, art films, radio plays, etc. They have been performed world-wide by numerous soloists and ensembles and by all Israeli orchestras including the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, The Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra, The Israel Chamber Orchestra, as well as the Berlin Radio Orchestra, the Saarland Radio Synphony Orchestra, the Brooklyn Philharmonic Orchestra, the Stuttgart Radio Orchestra, Bochum Symphony and others.

In his early works Avni followed the line of the so-called Mediterranean Style which was still prevalent in Israel in the 1950s. His encounter in the early 1960s with some of the newer trends in musical thinking, including the electronic medium, were a turning point in his style, which now became more abstract and focused on sonorism and post-Webern developments though preserving some of its former characteristics. Avni's interest in Jewish mysticism since the mid 1970s left a further mark on his musical language in which some neo-tonal elements manifest themselves in a new synthesis.

Avni is a recipient of several prizes, including the ACUM Prize for his life achievements (1986) and the Kuestermeier Prize awarded to him by the Germany-Israel Friendship Association (1990), The Israel Prime Minister's Prize for his life achievements (1998), the Culture Prize of the Saarland (1998) and the Israel Prize (2000).

Constantly active in Israel's public musical life, Tzvi Avni served in the past as Chairman of the Israel Composers' League and led the World Music Days which took place in Israel in 1980. For several years he was Chairman of the Music Committee of the National Council for Culture and Art, served twice as Chairman of the Jury of the Arthur Rubinstein International Piano Master Competition (in 1989 and in 1992) and is currently Chairman of the Directory Board of the Israel Jeunesses Musicales. He has been constantly lecturing and publishing articles on musical topics for professional musicians as well as for a general public.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tzvi_Avni

https://www.tzviavni-composer.com/home

Steven Barnett

Steve Barnett is known internationally as an award-winning independent recording producer for Minneapolis-based Barnett Music Productions. He received his second and third classical Grammy® awards for his production of Chanticleer’s world-premiere recording of Sir John Tavener’s “Lamentations and Praises” with the Orchestra of the Handel and Haydn Society of Boston, and received his first classical Grammy® for his production of Chanticleer’s “Colors of Love”. Both CDs are on the Warner Classics/Teldec label.

He was also a Grammy®-award nominee for his productions of “Walden Pond” (Dale Warland Singers on the Gothic label), “Our American Journey” (Chanticleer on the Teldec label), and an all-Argento orchestral/choral CD (Philip Brunelle conducting on Virgin Classics). In addition, he received the British Gramophone “Opera of the Year” award in London for his production of the world-premiere recording of Britten’s first opera Paul Bunyan (Philip Brunelle conducting, also on Virgin Classics). His major label production credits include CDs with Warner Classics, Teldec, Archiv, Virgin Classics, RCA/BMG “Red Seal”, Harmonia Mundi, PentaTone Classics, Gothic, Collins Classics (BMG), Avie, and also many independent labels.

Steve's recording productions include such ensembles and soloists as Chanticleer, Anonymous 4, Cantus, The Swingle Singers, The King’s Singers, The Dale Warland Singers, Philip Brunelle’s VocalEssence Ensemble Singers, The San Francisco Girls Chorus, Chicago A Cappella, The Princeton Singers, The Washington Bach Consort, The Cathedral Choral Society of the National Cathedral and Cappella Romana; the Minnesota Symphony Orchestra, Houston Symphony, Philharmonia Orchestra of London (as both conductor and producer), guitarist Sharon Isbin, the Newberry Consort, Vivica Genaux and Les Violons du Roy, the Rotterdam Philharmonic, Sopranos Joyce DiDonato, Susan Graham, Frederica Von Stade, composer/pianist Jake Heggie, members of the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, and the Chamber Orchestra of Lausanne, The Minnesota Opera (a world premiere opera recording), and the Royal Swedish Opera (including two world premiere opera recordings). He was the initial recording producer for the American Composer’s Forum’s independent innova records label.

For 25 years, Steve was music producer of the Peabody- and ASCAP Deems Taylor-award winning, internationally-broadcast chamber music program Saint Paul Sunday® on Public Radio.

As a Composer/Arranger/Conductor, Steve Barnett is also known internationally for his compositions and arrangements published by Oxford University Press, Boosey & Hawkes, Hinshaw Music, Transcontinental (distributed by Hal Leonard), and ADAR Music Ltd.

His orchestral commissions include performances by the New York Philharmonic, Minnesota Symphony Orchestra, Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, Kansas City Symphony, Baltimore Symphony, Phoenix Symphony, San Francisco Symphony, Cantor Benzion Miller and the Barcelona Philharmonic, and the San Antonio Symphony.

His choral commissions include performances and recordings by Chanticleer, The Dale Warland Singers, Philip Brunelle’s Ensemble Singers (VocalEssence), the San Francisco Girls Chorus, the Zamir Chorale and a number of other choruses. The Milken Archive of American Jewish Music chose Steve as one of the selected composer/arrangers whose recorded works appear on the Naxos label’s releases of the largest collection of original American Jewish music ever assembled.

He was Assistant Creative Director at Sound 80 Recording Studios for four years, composing, arranging and producing music for radio and TV commercials and industrial and commercial films.

Steve was also Music Director/Arranger/Conductor for Garrison Keillor’s A Prairie Home Companion, and for both national public radio musical variety programs, Good Evening and First House on the Right.

Steve was a choral director for twenty-two years, an Assistant Director of Bands at the University of Minnesota for two years, and conducted three Twin Cities-area community orchestras over a span of ten years.

Steve is a composition and early music graduate of the University of Minnesota and also studied jazz composition and arranging at the Eastman School of Music.

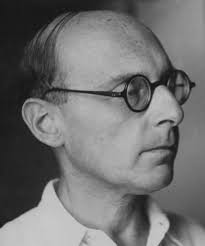

Paul Ben-Haim

Paul Ben-Haim: From Munich to Tel Aviv

-Joshua Jacobson

Paul Frankenburger was born in July 1897 in the Bavarian city of Munich. Munich was a city of high culture, and quite conservative in its tastes. Jews comprised about 2% of the population. Paul’s mother, Anna, came from an assimilated family, and most of her relatives had converted to Christianity.

Paul recalls that his father, Heinrich, although not observant, was a religious man, and attended synagogue regularly. It’s interesting to note that Heinrich, affiliated with the Liberal Jewish community of Munich, was indifferent or even hostile to the Zionist movement.

Heinrich’s father was strictly religious man who served his local synagogue in Uhlfeld as a ba’al tefillah – a volunteer but highly skilled leader of the prayers. Apparently he was a competent musician as well, playing both violin and flute and musically literate. Paul recalled, “The ultra-Orthodox disapproved of his singing in the synagogue from written music, and for this reason he came close to losing his position.”

Paul’s musical talent was soon evident. His violin teacher discovered that the child had perfect pitch. But the violin wasn’t enough for Paul. He wanted to explore harmony and switch to piano. Soon he was enrolled in the Music Academy of Munich where he concentrated on piano and composition. In his student years he was a prolific composer of Lieder (art songs).

In 1916 his music studies were interrupted when he was mobilized to serve as a soldier in an anti-aircraft unit fighting in France and Belgium. This was a traumatic experience for Paul. Not only the shock of battle, and Germany’s loss. He almost died in a gas attack. And his older brother died in combat. And while he was in the service his mother passed away at the age of 51.

Paul returned to Munich in 1918, walking by foot most of the 700 kilometer journey home. Ill and depressed, he found comfort in his music. He resumed his studies at the academy and graduated in June, 1920.

Within a year he had a job at the Munich opera as Korrepetitor -- coach and deputy conductor of the chorus. This was a great opportunity for Paul to work alongside great some of Europe’s greatest singers and conductors.

His next job was at the Augsburger Stadttheater as Third Kapellmeister and Choir Conductor. He received rave reviews for his conducting, and in 1929 he was appointed First Kapellmeister and immediately took the company on an international tour.

December 1929 he arrived in Merano, Italy with his opera company. He loved the city so much he returned there the following spring. He wrote an article for the Augsburg Opera House Bulletin, in which we begin to see Paul’s fondness for a Mediterranean climate:

How wonderful are the spring evenings in Merano! This is the real south, for which we long so eagerly; although it is not the classic south of Naples or Sicily, its charm bears not a trace of the north. Here is the magic of vineyards and of laurel, myrtle and almond trees, and skies as blue and as smooth as silk. Coming through the Brenner Pass, the glorious Italian breezes caress the brows of those coming from the misty, muddy grayness of the North.

But by 1931 the tide of Anti-Semitism was rising in Germany. Here is an excerpt from a review by Ulrich Herzog in the Neue Badische Landeszeitung of Mannheim: “Paul Frankenburger’s Psalm 126 sounded like an ecstatic hymn. Racially inferior art, of course, but sincere.” In 1931 the new director of the Augsburg Opera told Paul that his contract would be terminated at the end of the season, despite his great successes. He was now without a job.

March 1933 a Nazi government was elected in Bavaria. The racial laws were then applied to the Jewish community. Of the 9,000 Jews living in Munich, only about 800 left the city right away. 140 of them went to Palestine.

April 1933 –the German Musicians Union passed a resolution instructing all branches to work against “racially alien phenomena, Communist elements and people known to be associated with Marxism.”

Later that month Paul’s Concerto Grosso was performed by the Chemnitz orchestra. The Chemnitz newspaper published an article blasting the orchestra’s management for performing a work by a Jew.

Paul knew it was time to leave Germany and he decided to make an exploratory trip to Palestine. And of course Paul Frankenburger was meticulous in his preparations. From the composer’s autobiography:

Because of the rising tide of Jewish immigration from Germany, the English consul piled obstruction upon obstruction. … His first question was: What did I actually want to do in Palestine? I replied: ‘I want to see the country and investigate the possibilities of immigration.’ ‘Very well,’ he said, ‘I am prepared to give you a tourist visa — under the following conditions: 1. You may stay in the country for 6 weeks, and not one day longer. 2. You will submit a formal statement to the effect that you will not seek any employment in Palestine, and will refuse any job offered to you. 3. You or your father will deposit with me the sum of 10,000 marks to be forfeited if you violate any of these conditions.’

I collected the necessary things, I packed my bags, and on May 15 1933 I took the train from Munich to Trieste. On May 16 I embarked on the Italia, an old and small steamer…. This was the beginning of a five-day voyage from Trieste to Jaffa. I had a third-class ticket and was forced to sleep in a windowless cabin with 12 other men.

On the voyage he met a violinist, Simon Bakman, who was traveling to perform some concerts in Palestine. Simon invited Paul to be his accompanist. They did a few concerts on the boat and promised to meet again in Tel Aviv.

Paul landed in Jaffa and made his way to Tel Aviv. Paul wrote:

A truly modern European city is being built here on the sandy dunes with indescribable diligence and energy; a really impressive experience. The entire population here is Jewish: policemen, clerks, drivers, down to the last of the road-workers, all are Jews. By the way, the Palestinian Jews, especially the teenagers, are an exceptionally beautiful and sturdy race; the scruffy, often un-aesthetic exterior of many Jews from Eastern Europe no longer exists here!

Paul loved the Tel Aviv beach. After settling in Tel Aviv he went swimming in the beach every day, winter and summer!

He was welcomed by many refugees from Germany. Among them was Moshe Hopenko, who owned a music store and was the manager for Simon Bakman, the violinist Paul had met on the boat. From the composer’s autobiography:

The next day I met Simon Bakman at Mr. Hopenko’s, that is, in his music shop. … Mr. Hopenko welcomed me in a most friendly and pleasant manner. We fixed our concert dates: two in Tel Aviv, one in Jerusalem, and one in Haifa. Now that my name was about to appear on posters and in the press, the problem arose; I had been forbidden to accept employment of any kind! Mr. Hopenko knew a way out. ‘Very simple,’ he said. ‘change your name!’ ‘But how?’ I asked. ‘What is your father’s name?’ he asked. ‘Heinrich,’ I replied. ‘Haim in Hebrew.’ ‘Well then,’ said Hopenko, ‘You’ll be called Ben-Haim.’

Paul wrote a letter to his father at the end of June 1933. “I can already see clearly that I will move here. This will not be easy. Everyone has close links with the country in which he grew up and whose culture he has absorbed, but the order of the day is: look ahead, not back. Even if it is difficult.”

Upon his return to Munich, Paul assembled all his documents and his compositions. The process of obtaining all the papers needed for immigration took a long time, but on the last day of October he finally got permission from the British consulate, and left for Palestine. He was the first notable composer to reach Palestine from Germany after the Nazis came to power. But others soon followed. The very next day Karl Salomon arrived. And within the next 2 years Heinrich Jacoby, Joseph Tal (Gruenthal) and Haim (Heinz) Alexander.

From the composer’s autobiography:

I taught 6 to 8 pupils at Hopenko’s Shulamit conservatory. The students were not particularly gifted and it was not easy for me to work with beginners. Before long, I began to teach classes in music theory. This was even harder for me, since I had to explain a complex subject in my elementary Hebrew and at the same time maintain discipline in a class of boisterous 12 to 15 year old children. I managed to overcome the difficulties to some extent, but I would not like to do it again.

Between 1932 and 1939 more than 300,00 Jewish immigrants came to Palestine, fleeing Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia. These were, for the most part, not Zionists, and many came from assimilated families. But once settled, many, like Paul Ben-Haim, were quite taken with the Zionist enterprise and their quest to create a new culture.

Many Israeli composers were searching for a new style – one that would blend elements of East and West: using the forms of European music, coloured with elements of Middle Eastern music: the scales, rhythms, melodies, timbre, instrumentation, texture.

They took as their inspiration an essay by, of all people, Friedrich Nietzsche. Once a fan of Richard Wagner’s work, Nietzsche was now turning against the German composer. Now he’s excited about Bizet’s opera, Carmen. Nietzsche wrote:

What it [Carmen] has above all else is that which belongs to sub-tropical zones—that dryness of atmosphere, that limpidezza of the air. Here in every respect the climate is altered. Here another kind of sensuality, another kind of sensitiveness, and another kind of cheerfulness make their appeal. This music [Carmen] is gay, but not in a French or German way. Its gaiety is African. … I envy Bizet for having had the courage of this sensitiveness, which hitherto in the cultured music of Europe has found no means of expression—of this southern, tawny, sunburnt sensitiveness. … What a joy the golden afternoon of its happiness is to us! …Il faut mediterraniser la musique: and I have reasons for this principle. The return to nature, health, good spirits, youth, virtue.

Compare that to Ben-Haim’s comments about Italy 1930. “How wonderful are the spring evenings in Merano! This is the real south, for which we long so eagerly; …, its charm bears not a trace of the north. Here is the magic of vineyards and of laurel, myrtle and almond trees, and skies as blue and as smooth as silk. …, the glorious Italian breezes caress the brows of those coming from the misty, muddy grayness of the North.”

The Israeli composers and critics dubbed this new style “Eastern Mediterranean” תכון מזרח.

Writer Max Brod described this sound as (1) southern, infused with the bright light of the Mediterranean air, lucid, striving for clarity; (2) the rhythm … the obstinate repetition, but also the manifold, ceaseless variation which enchants by its apparent freedom from rule, and impulsiveness. (3) The structure of the movement is sometimes linear unison, or at least not polyphonically overburdened. (4) The influence exerted by the melodies of the Yemenite Jews, … the return to ancient modes, … in all these respects, lines of connection can be drawn with Arabic music ….

These European musicians were fascinated by the music they heard around them: music of the Christian and Moslem Arabs, as well as the music of the Jewish Arabs.

Ben-Haim wrote:

These are the features typical of Israeli [classical] music: A special orchestration, which includes a mixture of oriental sonorities; preference is accorded to the woodwinds (such as oboe and flute), whose origin is undoubtedly in the East. The musical tradition of the oriental communities has been relatively well-preserved in its purity, due to the isolation which they imposed upon themselves, and their non-involvement with the gentiles... if any influence existed, it came from the Arab side. We should not reject such influence. On the contrary: we must also take an interest in Arab folklore. If we wish to speak of an Israeli revival, we should welcome all Semitic influences, and oppose western ones.

The one person who exerted perhaps the greatest influence on Ben-Haim and his fellow immigrant composers was Bracha Zephira. Zephira was born into a Yemenite family in Jerusalem in 1911. Her parents died when she was a small child and she lived in a series of foster homes of Yemenite, Persian and Sephardi families. In 1924 she was sent to a boarding school near Hadera, where she was again surrounded by children from Middle-Eastern backgrounds.

In the 1930s she began to perform Oriental Jewish songs in concert, accompanied by the pianist Nahum Nardi, first in Europe and then back in Palestine. Soon Zefira was performing with other European composers, who were enchanted by her exotic music and her dark beauty. Most prominent among these collaborators was Paul Ben-Haim.

In the summer of 1966 the National Federation of Temple Youth, a branch of American Reform Judaism, commissioned Ben-Haim to compose a setting of the Friday night liturgy, according to the American Reform prayer book. The composer wrote:

I have tried to set the prayers to music in as simple and modest a style as possible, to express the spirit of the Jewish liturgy.…According to the request of the commissioning body I gave an especially simple character to the concluding hymn, for which I used motives of an ancient Sephardic tune. For the refrain of the Sabbath hymn (“Lecha Dodi”) I have used an old traditional melody sung by Sephardi Jews to a different text (“Yedid Nefesh”). In no other parts than the two mentioned above were traditional melodies quoted or used, but I have tried everywhere to keep my music faithful to the spirit of our religious tradition.

Kabbalat Shabbat had its first performance April 24, 1968, at Lincoln Center in New York, conductor Abraham Kaplan and Cantor Ray Smolover. Ten days later performed at Temple Israel Boston as part of a service. Herbert Fromm (Ben-Haim’s old friend) conducted, and Bill Marel was the cantor.

May 1968 the president of the republic of West Germany awarded Paul Ben-Haim Germany’s highest honor: Das Verdienstkreuz, erste Klasse (The Cross of Distinction first class).

When Ben-Haim was about to turn 75, he received another honor: the city of Munich invited him to visit as an honoured guest. July, 1971 Dr. Hans Joachim Vogel, the head of the Munich City Council (Der Alt Oberbürgermeister), wrote in his invitation to Ben Haim, “During the time I have been the city’s senior counsellor …I have paid special attention to the renewal and cultivation of contacts with past residents of our city, forced to leave after 1933 for political, racial or religious reasons.” And on May 4, 1972, The City of Munich presented a special concert of Ben-Haim’s music in his honor.

Sadly, A few days later he was walking down the street in Munich, reminiscing about his childhood, when he was struck by a car. Hospitalized. Left him partially paralyzed and confined to a wheelchair..

But he continued to compose until his death January 14, 1984 at the age of 87. His legacy can be summed up in this wonderful quote:

I am of the West by birth and education, but I stem from the East and live in the East. I regard this as a great blessing indeed and it makes me feel grateful. The problem of synthesis of East and West occupies musicians all over the world. If we-thanks to our living in a country that forms a bridge between East and West-can provide a modest contribution to such a synthesis in music, we shall be very happy.

Gradenwitz, Peter. Paul Ben Haim. Tel Aviv: Israeli Music Publications, 1967.

Guttman, Hadassah. The Music of Paul Ben-Haim: a performance guide. Metuchen, NJ: The Scarecrow Press, 1992.

Hirshberg, Jehoash. Paul Ben-Haim: His Life and Works. Translated by Nathan Friedgut. Jerusalem: Israeli Music Publications, 1990.

Plotinsky, Anita Heppner. “The Choral Music of Paul Ben-Haim.” American Choral Review, 16 (1974): 3-10.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Ben-Haim

Leonard Bernstein

Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) was born in Lawrence, Massachusetts on August 25, 1918 to Sam and Jennie Bernstein, Jewish immigrants from the Ukraine. Lenny grew up in the Boston area, his family moving frequently—first to Mattapan, then Allston, Roxbury, and Newton. Summers were spent at the family home on a lake in Sharon.

Bernstein was a musical prodigy. As a child he loved to play the piano and organize impromptu concerts and even musicals and operas, featuring himself, naturally, as the star, and with his family and friends taking the supporting roles.

Bernstein said that the first time he heard great music was as a child, listening to the organ, cantor and choir at Congregation Mishkan Tefila under the direction of Solomon Braslavsky. He also attended Hebrew School at Mishkan Tefila and celebrated his bar mitzvah there.

His father Sam came from a long line of rabbis, and Sam himself was deeply involved in the study of Jewish texts, especially the Talmud. But while his passion was Talmud, his work was the beauty supply business, The Sam Bernstein Hair Company. Naturally, Sam wanted Lenny to go into the family business, or if not that, then he should be a rabbi. He simply couldn’t understand his son’s interest in music. Years later in an interview, Sam and asked why he discouraged his son from pursuing a career in music. He replied, “How did I know he would grow up to become Leonard Bernstein?”

In 1957 Bernstein was named Music Director of the New York Philharmonic, becoming the first American-born music director of any major symphony orchestra. Bernstein was a great conductor, but he was also a great and devoted teacher, a brilliant concert pianist, and a successful composer of both Broadway and “classical” music.

Bernstein also strongly identified Jewishly and was a passionate supporter of Israel. He was a frequent visitor to Israel, guest conducting the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra. And many of his compositions have Jewish content, including his Jeremiah and Kaddish symphonies, settings of the prayers Hashkivenu and Yigdal, arrangements of Israeli songs Simhu Na and Reena, a piano suite entitled Four Sabras, the Dybbuk ballet, a chamber work entitled Hallil, and the Chichester Psalms. In 1948 Bernstein and Jerome Robbins were working on a musical that was to be called East Side Story. It was to be “a modern version of Romeo and Juliet set in the slums at the coincidence of Easter-Passover celebrations. Feelings run high between Jews and Catholics. Juliet is Jewish. Street brawls, double death—it all fits.”

https://leonardbernstein.com

https://www.milkenarchive.org/artists/view/leonard-bernstein/

Ernest Bloch

The creator of the greatest Jewish concert music of the 20th century was undoubtedly the Swiss-American composer, Ernest Bloch. Born in Geneva, Switzerland on July 24, 1880, he was the youngest of three children. Although his father was actively involved in the Jewish community, Ernest's interests were focused on music. By the age of nine, he was already playing the violin and composing. To say that his father did not encourage his musical talent would be an understatement. But despite his father's objections (Maurice referred to his son's compositions as Scheissmusik), Ernest continued his musical training, moving from Geneva, where he had studied with Émile Dalcroze to Brussels to work with Eugene Ysaÿe, Frankfurt with Ivan Knorr, Munich with Ludwig Thuille, and Paris where he associated with Claude Debussy.

While in Paris, Bloch renewed his friendship with Edmond Fleg (1874-1963), a poet and historian and a fellow Genevan. Fleg was to plant seeds in his friend's soul that would bear fruit for many years and change the course of the composer's life. In 1894 Capt. Alfred Dreyfus had been put on trial in Paris on charges of treason. He was quickly convicted and sentenced to life in a prison colony. But within a few years evidence was brought forth proving that the documents that had incriminated Dreyfus were the forgeries of an anti-Semite. Paris was in turmoil over these revelations, and many Jews, Edmond Fleg among them, became ardent nationalists.

It was Fleg's influence that caused Bloch to rediscover his Jewish roots and proclaim his ethnic pride. In 1906 Bloch wrote a letter to Fleg in which he proclaimed, "I have read the Bible … and an immense sense of pride surged in me. My entire being vibrated; it is a revelation. … I would find myself again a Jew, raise my head proudly as a Jew." In a subsequent letter to Fleg (1911) Bloch formulated his new artistic manifesto.

I notice here and there themes that are without my willing it, for the greater part Jewish, and which begin to make themselves precise and indicate the instinctive and also conscious direction in which I am going. I do not search to produce a form, I am producing nothing so far, but I feel that the hour will come… There will be Jewish rhapsodies for orchestra, Jewish poems, dances mainly, poems for voices for which I have not the words, but I would wish them Hebraic. All my musical Bible shall come, and I would let sing in me these secular chants where will vibrate all the Jewish soul… I think that I shall write one day songs to be sung at the synagogue in part by the minister, in part by the faithful. It is really strange that all this comes out slowly, this impulse that has chosen me, who all my life have been a stranger to all that is Jewish.

Bloch's terminology is telling. He writes that he did not choose to become a composer of Jewish music, but rather that the impulse had chosen him. Indeed, Bloch had no sympathy for nationalist composers who deliberately tried to insert folk-like themes into their works; Bloch was convinced that if a composition were to be honest and organic, the Jewish element must be integrated subconsciously into the creative process.

To our ears his use of the word "race" may sound alarming and politically incorrect. But Bloch was formulating his thoughts at a time when Europe was formulating a new form of Jew hatred. The term anti-Semitism didn’t make its first appearance until the year 1879, only one year before the composer's birth. Prior to the Enlightenment, anti-Jewish attacks had been based on religious intolerance or suspicions of divided national loyalty. But in the new liberal Europe, scorn of the Jew would be based on the inferiority of the Semites as a race. The "scientific" study of racial differences led to Joseph-Arthur Gobineau's, Essay on the Inequality of Human Races (1853) and Richard Wagner's notorious essay, "Jewishness in Music" (1850), in which he argued that Jews were incapable of creating any original music within the European cultivated tradition. As to the distinctive liturgical music of the Jews, Wagner considered it "a travesty … a repugnant gurgle, yodel and cackle."

Bloch accepted the idea of the racial distinctiveness of the Jews, but, unlike Wagner, he had an appreciation for traditional synagogue chant, and believed that a Jew who is steeped in that tradition not only could create symphonic music, but could not help but create a work of art that somehow incorporates this traditional foundation.

In 1916 he was quoted in an interview in the Boston Post.

Racial consciousness is something that every great artist must have. A tree must have its roots deep down in its soil. A composer who says something is not only himself. He is his forefathers! He is his people! Then his message takes on a vitality and significance which nothing else can give it, and which is absolutely essential in great art. I try to compose with this in mind. I am a Jew. I have the virtues and defects of the Jew. It is my own belief that when I am most Jewish I compose most effectively.

From 1912 to 1916 Bloch composed a series of works based on Jewish themes, including The Israel Symphony (1912-1916), Three Psalms (1912-1914), Schelomo (1916), the first string quartet (1916), and Three Jewish Poems for Orchestra (1913).

In 1916 Bloch came to New York to conduct a ballet orchestra. He was so taken by the atmosphere and opportunities that the following year he fetched his family and moved permanently to the United States. For three years he was an instructor at the Mannes School of Music in Manhattan. Then, from 1920 to 1925, he served as the founding director of the Cleveland Institute of Music. In 1925 he moved to San Francisco to become Director of the San Francisco Conservatory. In 1930, thanks to a generous trust fund administered though the University of California at Berkeley, Bloch was able to resign his position from the San Francisco Conservatory and devote himself full-time to composing and conducting. After nearly a decade in Europe, Bloch returned to California, to teach an annual workshop for composers at Berkeley. In 1952 he retired from teaching altogether and moved to a reclusive life in Oregon. Bloch died July 15, 1959 in Portland, Oregon.

Bloch's greatest legacy may be the impressive body of compositions. But in addition, he affected the lives of so many Americans through his inspiring conducting of choruses and orchestras, and through his teaching. The roster of his students reads like a veritable who's who of American composers, including George Antheil, Henry Cowell, Frederick Jacobi, Leon Kirchner, Douglas Moore, Quincy Porter, Bernard Rogers, Roger Sessions, and Randall Thompson.

In 1929 Bloch's friend, Cantor Reuben Rinder of Temple Emanu-El in San Francisco, commissioned him to write a setting of the Sabbath morning liturgy. The composer took the project very seriously.

I am still studying my Hebrew text. I have now memorized entirely the whole service in Hebrew… I know its significance word by word. … But what is more important, I have absorbed it to the point that it has become mine and as if it were the very expression of my soul. It far surpasses a Hebrew Service now. It has become a cosmic poem, a glorification of the laws of the Universe … the very text I was after since the age of ten … a dream of stars, of forces … the Primordial Element … before the worlds existed. … It has become a 'private affair' between God and me.

It took Bloch four years to complete his Sacred Service (Avodat Ha-kodesh), with most of the work done at his retreat in the Swiss Alps. In 1934 he conducted the first performances in concert halls in Turin, Naples, New York, Milan, and London. Ironically, it wasn't until 1938 that Temple Emanu-El was able to present the work it had commissioned. But perhaps this grand work, with its universal themes, its post-romantic organic conception, scored for large orchestra, chorus, and baritone soloist, was more appropriate for the concert stage than for the synagogue bimah. Bloch himself considered it more a sacred Hebrew oratorio than a Jewish liturgical service. He once said, "I am completely submerged in my great Jewish 'Oratorio,' on an enormous Hebrew text, and more cosmic and universal than Jewish."

Bloch's "enormous Hebrew text" was supposed to be the Sabbath morning liturgy of the American Reform synagogue, as it appeared in the Union Prayer Book. But by setting only the Hebrew texts, Bloch significantly departed from the Reform liturgy, which was designed to be conducted primarily in English. Furthermore, by creating a major work that was to be performed without interruption, the composer left no room for certain key parts of the service, including the Torah reading and the sermon. In this respect, at least, Bloch's Service shares a fate with Beethoven's Missa Solemnis: its scope is too grandiose and its message is too universal for the liturgical function upon which it was based. Indeed, Bloch said that the five parts of the Service "have to be played without interruption, as a unity … like the Mass of the Catholics."

Unifying the Service is a six-note motif: G-A-C-B-A-G, which Bloch weaves with masterful contrapuntal skill and is heard on nearly every page of the score. While the six-note motif may be thought of as representing the universal message of the Service, another, more sinuous melody represents the more personal, the specifically Jewish aspect. This melody is less rigid rhythmically, and more chromatic, evoking the modes of traditional synagogue chant.

The Service opens with what the composer called, "a kind of 'Pastorale'—in the desert perhaps—The Temple of God in 'Nature.'" The voices intone Mah Tovu ("How goodly are thy tents," a traditional prayer recited on entering a synagogue, but absent from the Union Prayer Book), and continue with Barekhu (call to prayer), and the Shema (Jewish Credo) and its blessings. "Here one feels God Himself knows how beautiful life can be made with joy inside, not through external possessions." The movement ends with Tsur Yisroel ("Rock of Israel"), the only part of the Service based on a traditional synagogue melody, a deliciously understated cantorial recitative. Bloch called it a response to "all the misery, the sufferings of Humanity—as represented by a crowd of poor, hungry, persecuted people."

The second movement comprises the central portion of any Jewish liturgy, the Tefillah. Bloch chose to set only the Kedushah (Sanctification), a trope traditionally chanted responsively by cantor and congregation. Here again we sense the composer's universalization of the prayer. He called it, "a dialogue between God and Man, the chorus discovering the law of the atom, the stars, the whole universe, the One, He our God."

The third movement starts with a "silent meditation." The orchestra alone is heard, allowing the audience a moment to formulate their own thoughts, perhaps as a substitute for the liturgical silent Tefillah. Then the choir, a cappella, quietly intones Yihyu Lerotson, the prayer for acceptance that follows the Tefillah. The composer called this section "a silent meditation which comes in before you take your soul out and look at what it contains."

A transition leads to the most majestic section of the liturgy—the service in which the Torah is taken from the ark and paraded through the congregation. Bloch's description is worth quoting in full.

When I read “Lift up your heads, O ye gates and be ye lifted up ye everlasting doors and the King of Glory shall come in,” I could not understand what this was about. It mystified, puzzled and worried me. I was in the Swiss mountains at the time; the day was foggy, the fir trees drooped, the landscape was covered with sadness, I could not see the light. Suddenly a wind came up, the clouds in the sky parted and the sun was over everything. I understood. I felt God was within me at that time in lifting up the clouds. We were in a fog, we could not see the Truth, nor understand God and life. But when the clouds lift from out of our mind and life, and our hearts become as a little child, then the Truth will come in as a King of Glory.

The fourth movement was inspired by the ceremony of returning the Torah to the ark. It ends with Ets Chayim Hi, which Bloch called a “peace song.” Indeed, Bloch ends the movement with ten repetitions of the word “sholom.”

The fifth and final movement is the most daring of the Service, and took Bloch the longest to compose. It begins with a recapitulation of the pastoral mood of the opening, after which the cantor and choir sing the Reform “Adoration,” based on the traditional Oleynu prayer. Now for the first time Bloch introduces the English text of the Union Prayer Book, to be recited by the “minister” over the orchestral interlude. Yet this “spoken voice” part is notated with specified pitches and rhythms. The chorus returns (in Hebrew) with the explosive conclusion to the Oleynu prayer. “Then there is a terrible crash, as if suddenly poor, fleshy man thinks of himself, his fears—death.” The minister returns to recite, in English, a prologue to the Mourners’ Kaddish. But in place of the expected Kaddish, the chorus recapitulates the Tsur Yisroel from the end of the first movement. Bloch called this “the supplication of mankind, its cry towards God for help, for an explanation of this sad world—the reason for our suffering.”

After an ominous silence—from very far away—out of time—out of Space—above Time and Space, a kind of collective voice rises, mysteriously—Is it the key—the answer—the explanation? This is the beautiful poem, Adon Olom—a philosophy or metaphysics, which outgrows all creeds, all religions, all Science…

Bloch found himself at an impasse here. How was he to end this great work of his?

When I saw the last small violet in the field, dead, after giving everything it could, I too thought I was never going to finish [my] work. The last twenty-five measures took me two years to write. I wanted something lyrical, a joy for the people. Two years of groping in the darkness it took to deliver the message to the people: the conquering of death, life, suffering with the highest sense and in the highest proportion.

The concluding hymn of the Union Prayer Book (Eyn Keloheynu)did not provide Bloch with the answer he was seeking. In its place, he substituted the hymn that appears in the Reform liturgy as the conclusion for the Sabbath evening service. Adon Olom was his answer. But this was not to be the typical setting of Adon Olom, sung rather mindlessly by the congregation as a strophic hymn. Bloch is probably the only composer who has dared attempt a literal setting of this cosmic poem. This is not functional liturgical music. With dramatic gestures Bloch paints an eerie picture of a world “before any living being was created,” and then a world “after all things shall cease to exist.” He then applies a more comforting brush to “He is my God, my living Redeemer, my comfort in time of sorrow…the LORD is with me, I shall have no fear.”

Then after the orchestra and chorus give this message of faith, hope and courage, we must send people back to their routine of living, cooking, laundry and so on. Thus, the priest gives a benediction, the chorus answers, “Amen,” and they leave.

It is a whole drama in itself. … For fifty minutes I hope it will bring to the souls, minds and hearts of the people, a little more confidence, make them a little more kind and indulgent than they were and bring them peace.

Last year an informal search yielded a startling discovery: Bloch's Sacred Service had not been performed in concert in Boston since Zamir's last presentation of the work in 1994. Why isn't the Sacred Service performed more often? Perhaps its blood is too rich for most synagogues. Perhaps it appears too exotic for most symphonies and choral societies. As we were making plans for our anniversary concert, I knew that the Sacred Service had to be on the program.

For further reading:

Bloch, Suzanne and Irene Heskes. Ernest Bloch, Creative Spirit: A Program Source Book. New York: Jewish Music Council of the National Jewish Welfare Board, 1976.

Fromm, Herbert. On Jewish Music. Bloch Publishing Co., 1978.

Knapp, Alexander. "The Jewishness of Bloch: Subconscious or Conscious?", Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association, 97 (1970-71), 99-112.

Móricz, Klára. “Jewish Nationalism in Twentieth-Century Art Music.” Ph.D. dissertation, The University of California, Berkeley, 1999.

Schiller, David Michael. Bloch, Schoenberg, Bernstein: Assimilating Jewish Music. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Strassburg, Robert. Ernest Bloch. Los Angeles: California State University, 1977.

Ward, Seth. "The Liturgy of Bloch's Avodath Ha-Kodesh." Modern Judaism 23:3 (October 2003), 243-263

Solomon Braslavsky

Prof. Solomon Braslavsky (1887-1975) was born in Ukraine and given his first music education by his cantor-father. Braslavsky then studied music in Vienna at the Royal imperial Academy of Music and at the University of Vienna. In 1928 Rabbi Herman Rubenovitz brought Braslavsky to Boston to serve as music director at Congregation Mishkan Tefila, where he remained for his entire career. Braslavsky created an impressive musical service of superior quality, and he held the professional choir to the highest standard. Mishkan Tefila’s organ was truly magnificent, second only in size and quality to that of Symphony Hall in Boston. Much of the music heard in the services was the product of the great 19th century masters, including Sulzer and Lewandowski. But Braslavsky also contributed many of his own compositions. When Leonard Bernstein was a child, the family synagogue was Mishkan Tefila. And Bernstein recollected that the first time he heard great music was as a child, listening to the organ and cantor and choir, all under the direction of Prof. Braslavsky. “I used to weep just listening to the choir, cantor and organ thundering out—it was a big influence on me,” he said. “I may have heard greater masterpieces performed since then, and under more impressive circumstances, but I have never been more deeply moved.” Bernstein remained friendly with Braslavsky (whom he affectionately called, “Brassy”) throughout his life.

Yehezkel Braun

Yehezkel Braun (1922-2014) was born in Breslau and the age of two was brought to Israel, where he found himself in close contact with East-Mediterranean traditional musics. The influence of this background is clearly felt in his compositions. He is a graduate of the Israel Academy of Music and holds a Master's degree in Classical Studies from Tel Aviv University. In 1975 he studied Gregorian chant with Dom Jean Claire at the Benedictine monastery of Solesmes in France. His main academic interests were traditional Jewish melodies and Gregorian chant. He lectured on these and other subjects, at universities and congresses in England, France, the United States and Germany. Yehezkel Braun taught for many years at Tel Aviv University. In 2001 he was awarded the prestigious Israel Prize. (The Israel Prize is the most highly regarded award in Israel. It was first awarded in 1953 and has been awarded every year since then on the eve of the Israeli Day of Independence. The prize is presented to the recipient before the Knesset, Prime Minister, President, and Supreme Court of Israel.) Considered to be one of Israel's greatest composers, Braun's music is delightfully lyrical and reflects his passion for traditional Jewish chant.

https://www.milkenarchive.org/artists/view/yehezkel-braun/

https://www.jewish-music.huji.ac.il/content/yehezkiel-braun

David Burger

David Burger (b. 1950) is a composer whose works have been performed in Carnegie, Avery Fisher and Jordan Halls, in Europe and in Israel. He sang in the first concert on the newly liberated Mt. Scopus in 1967 and, two years later, began composing professionally for Richie Havens when he wrote the charts for Freedom from the movie Woodstock. Both of these events contributed to his musical sensibility.

Burger wrote and performed with a number of fusion bands in the 1970’s, during which time he studied under the major theorists Felix Salzer and Jacques Louis Monod and earned a Masters Degree in music theory from Queens College. He is known for his choral works, which have a particularly American vocabulary, most notably The Israel Trilogy (Hatikvah Hanoshanah, The Declaration of Independence of Israel and T’filah), and for many songs that express the emotional depth of American Jewry’s passion for Israel. He is the first person to have deduced and set the vocalizations of Psalms 151, 154 and 155 from the Dead Sea Scrolls.

In recent years, Mr. Burger has orchestrated works by David Crosby, directed and written the scores for the film Dark Angel and for Birthright, a modern ballet by choreographer Sasha Spielvogel. Most recently, he has written and directed two musicals based on Macbeth and Romeo and Juliet. He is the recipient of numerous awards, grants and commissions and his biography is found in Who’s Who in America and in Who’s Who Among America’s Teachers. Mr. Burger lives and teaches in New York City.

Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco

Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco (1895-1968)

Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco was born in Florence to an Italian Sephardi Jewish family that had been in Tuscany for more than 400 years, his father’s forebears having resettled there as refugees following the Spanish Expulsion in 1492. As a child, he began piano lessons with his mother and was composing by the age of nine. Although there is no record of professional artistic tradition in the family, his maternal grandfather apparently harbored an almost secret interest in synagogue music. This was learned many years after his death, when Mario discovered a small notebook in which his grandfather had notated musically several Hebrew prayers. Mario later recalled that this incident made a profound impression on him: “one of the deepest emotions of my life … a precious heritage.” It inspired his first Jewish composition, his Hebrew rhapsody Danze del re David, for solo piano, as well as Prayers My Grandfather Wrote (1962).

Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s formal musical education began at the Institute Musicale Cherubini in Florence in 1909, leading to a degree in piano in 1914 and a composition diploma in 1918 from Liceo Musicale di Bologna. His growing European reputation was aided by performances of his music under the aegis of the International Society of Contemporary Music, formed after the First World War in part to reunite composers from previously belligerent nations.

Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s first large-scale work—a comic opera based on the Machiavelli play La Mandragoa—was awarded the Concorso Lirico Nazionale prize. Also active as a performer and critic, he accompanied such internationally famous artists as Lotte Lehman, Elisabeth Schumann, and Gregor Piatigorsky; played in the Italian premiere of Stravinsky’s Les Noces;gave solo piano recitals; and wrote for several Italian journals. A prominent European music historian has called Castelnuovo-Tedesco “the most talented exponent of the Italian avant-garde of the time [1920s].” Yet his music has been described as progressive, Postimpressionist, neo-Romantic, and/or neo-Classical. He is often associated most prominently with his works for classical guitar and his contributions to that repertoire, and it is probably upon that medium that his chief fame rests. His association with Andres Segovia resulted in his unintentionally neo-Classical Concerto in D for guitar (op. 99, 1939), and eventually in a catalogue of nearly 100 guitar works.

Castelnuovo-Tedesco wrote later in his career that he “never believed in modernism, nor in neo-Classicism, nor in any other ‘isms’”; that he found all means of expression valid and useful. He rejected the highly analytic and theoretical style that was in vogue among many 20th-century composers, and in general his musical approach was informed not by abstract concepts and procedures, but by extramusical ideas—literary or visual. He articulated three principal thematic inspirations at the core of his musical expression: 1) his Italian home region; 2) Shakespeare, with whose work he was fascinated from his youth; and 3) the Bible, not only the actual book and its narratives, but also the Jewish spiritual and liturgical heritage that had accumulated from and been inspired by it over the centuries. This natural gravitation toward biblical and Judaic subjects resulted in an oeuvre permeated by Jewish themes.

Though anti-Semitism sprouted more gradually in Italy than in other parts of Europe prior to the Rome-Berlin Axis Pact of 1937, by about 1933, ten years after the Italian Fascists had come to power, a specific Fascist attitude vis-à-vis the arts, later known as the Mystic of Fascism, had been formulated. This involved the controlled use of art as a propaganda tool. By 1938 Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s music was eliminated from radio, and performances were canceled—all prior to the announcement of the official anti-Semitic laws. When the 1938 Manifesto of Race was issued by the Mussolini government, the composer determined to leave Italy. In 1939, just before the German invasion of Poland and the commencement of the war, he and his family left for America. In 1940 Jascha Heifetz organized a contract between Castelnuovo-Tedesco and the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) film studio, launching his fifteen-year career as a major film composer. Between then and 1956 he was also associated with Columbia, Universal, Warner Bros., Twentieth Century Fox, and CBS, working on scores as composer, assistant, or collaborator for some 200 films. In addition, his influence as a teacher of many other “Hollywood” composers was significant—among them such people as Henry Mancini, Jerry Goldsmith, Nelson Riddle, John Williams, and André Previn.

A host of refugee composers from Germany, Austria, and other Nazi-affected lands had settled in Los Angeles during the 1930s, and many took advantage of the opportunity to devote their talents at least in part to film. The list includes such “originally classical” composers as Korngold, Goldmark, Steiner, Toch, and Milhaud. Although Castelnuovo-Tedesco later sought to shrug off his Hollywood experience as artistically insignificant, critical assessments point to the film industry as having both defined his American career and affected his musical style in general. In fact, he saw film originally as an opportunity for genuine artistic creativity—an alternative medium to opera (which he viewed as inherently European) for the development of a manifestly American form of expression.

Historian James Westby, an authority on Castelnuovo-Tedesco, aptly sums up the composer’s American experience and its relation to his Jewish sensitivity, quoting from his memoirs:

For Castelnuovo-Tedesco, composition in America became “an act of faith,” an act born out of “the faith I inherited from my father, from my mother, from my grandfather, and which is so well expressed in the words of the Psalm which my grandfather used to sing [part of the grace after meals]: ‘I have been young and now I am old, yet I have not seen the just abandoned.’"

By: Neil W. Levin

Aharon Charlap

(Aaron Harlap) (b. 1941)

Aharon Harlap was born in 1941 in Canada, where he began his musical career as a pianist. In 1963 he completed his studies at the University of Manitoba, Canada, majoring in Mathematics and Music. In 1964 he immigrated to Israel. His composition teachers have been P. Racine Fricker, at the Royal College of Music in London, England, and Oedoen Partos at the Rubin Academy of Music in Tel Aviv. He studied conducting with Sir Adrian Boult in London, Hans Swarowsky in Vienna, and Gary Bertini in Israel. Aharon Harlap is well known as a a choral, operatic and orchestral conductor, and has been guest conductor of orchestras and opera in Canada, the United States, Europe and South Africa. In Israel he has been guest conductor of all the important orchestras, including the Israeli Philharmonic Orchestra. As a composer, Harlap's works have been performed frequently in the aforementioned countries, as well as in Israel, and include compositions for choir, chamber ensembles, and symphonic orchestra. In 1979 be was awarded a prize in an international competition based on the subject of "Holocaust and Revival" for his Oratorio "The Fire and the Mountains" (text: Israel Eliraz), and in 1983 received the ACUM Prize for "Three Songs" for mezzo-soprano and symphony orchestra. In 1993, he received the Mark Lavry Prize for composition, offered by the Haifa Municipality, for his choral-orchestral work "For dust you are, and to dust you shall return". In 1997 he was awarded a prize for his Opera "Therese Raquin" (based on the novel by Emile Zola), sponsored by the New Israeli Opera and the Israel Music Institute, and in the same year was awarded the ACUM Prize for his Clarinet Concerto. In 1999, he received the coveted Prime Minister's Prize for Composition. At present, Aharon Harlap is a senior lecturer in conducting at the Rubin Academy of Music in Jerusalem, where he also holds the position of head of the Opera Department. He is also music director and conductor of the Kfar Saba Chamber Choir and "Bel Canto" - the Israeli Male Choir, Kfar Saba.

Charles Davidson

Charles Davidson (b. 1929)

Charles Davidson is one of the most frequently commissioned composers by synagogues, cantors, and Jewish organizations, as well as by general secular choruses across America. He was one of the first graduates of the Jewish Theological Seminary’s Cantors Institute (now the H. L. Miller Cantorial School), where he later also received his doctorate in sacred music and where he has served on the faculty since 1977 (now Nathan Cummings Professor). Early in his career, Cantor Davidson became the music director and conductor of the International Zionist Federation Association Orchestra at the University of Pittsburgh and of the Hadassah Choral Society, and director of the Pittsburgh Contemporary Dance Association. Prior to his formal cantorial training at the seminary, he was a student at the unique Brandeis Arts Institute (a division of the Brandeis Camp Institute) in Santa Susana, California. The program there—under the direction of the conductor and composer Max Helfman—provided a rich and exciting forum for Jewish arts by bringing established Jewish musicians, dancers, and other artists of that period together with college-age students in an effort to broaden their creative horizons in the context of contemporary Jewish expression. Davidson and other future composers of distinction, including Yehudi Wyner and Jack Gottlieb, were able to benefit from the influence and tutelage of distinguished resident artists—among them Julius Chajes, Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, Erich Zeisl, and Heinrich Schalit.

Davidson’s monumental I Never Saw Another Butterfly, a setting of children’s poetry from the Terezin concentration camp in Czechoslovakia (where only 100 of the 15,000 imprisoned children survived), is unquestionably his best known and most celebrated work. It has been performed throughout the world (more than 2,500 performances) to consistent critical acclaim and is featured on no fewer than eight commercial recordings. It is also the subject of two award-winning PBS documentaries: The Journey of Butterfly and Butterfly Revisited. In 1991, following the collapse of the communist regime and the birth of the Czech Republic, it was performed at a special ceremony in the town of Terezin, presided over by the new president, Václav Havel, among other dignitaries, and attended by an audience of Holocaust survivors to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the Germans’ creation of the camp and ghetto. Performances followed at Smetana Hall in Prague and the Jesuit Church in Brno.

Davidson is a highly prolific composer and arranger. His catalogue contains more than three hundred works—including dozens of synagogue pieces, songs, choral cantatas, entire services, Psalm settings, musical plays, theatrical children’s presentations, instrumental pieces, and a one-act opera based on Isaac Bashevis Singer’s story Gimpel the Fool. Among the many memorable works in addition to those recorded for the Milken Archive series are The Trial of Anatole Sharansky; Night of Broken Glass, an oratorio in commemoration of Kristallnacht; Hush of Midnight: An American Selihot Service; L’David Mizmor, a service commissioned by the Park Avenue Synagogue; Libi B’Mizrach, a Sephardi synagogue service; and a service in Hassidic style. His oeuvre also includes a number of secular and even non-Jewish holiday choral settings that are performed often by high school and college choirs.

Cantor Davidson is the editor of Gates of Song, a collection of congregational melodies and hymns, author of the book From Szatmar to the New World: Max Wohlberg—American Cantor, and author of several cantorial textbooks. He served with distinction as hazzan of Congregation Adath Jeshurun in Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, from 1966 to 2004

By: Neil W. Levin

https://www.milkenarchive.org/artists/view/charles-davidson/

Eleanor Epstein

Eleanor Epstein is widely acknowledged as a master teacher and gifted choral conductor. A lifelong student of Jewish music and text, she grew up in a family steeped in Jewish learning and song – the heart of her work today.

Known for inspiring singers to connect deeply to both music and text, Eleanor works internationally as a guest conductor and artist-in-residence. She has collaborated and consulted with congregations, cantors and choirs, including The North American Jewish Choral Festival, Hebrew Union College, the Jewish Theological Seminary, and the Music Educators National Conference and the Soldiers’ Chorus of the United States Army.

A student of acclaimed American composer Alice Parker, Eleanor is committed to the preservation of Jewish folk melodies. Her choral settings of Jewish folk songs are performed throughout the world.

As artistic director and conductor of Zemer Chai, Eleanor creates an atmosphere where singers are encouraged to integrate their individual experiences with an emotional and intellectual understanding of the text and the melody, providing a special dimension to the choir’s music-making. Her passion for preserving and transmitting Jewish music inspires both her singers and her audiences and she is committed to the belief that music is a powerful force for building understanding. “Singing is an immediate way to build bridges between people.”

https://www.zemerchai.org/about-us

https://www.msac.org/arts-across-maryland/elevator-chat-eleanor-epstein-artistic-director-zemer-chai

Sharon Farber

Sharon Farber

Four - time Emmy Award Nominated, Winner of the 2013 Society of Composers and Lyricists Award for “Outstanding work in the Art of Film Music”, the 2012 Visionary Award In Music by The Women’s International Film & Television Showcase, winner of the Telly Award, and a member of The Academy of Motion Pictures, Sharon Farber is a celebrated Film, TV and concert music composer.

Farber began her musical career at the age of seven, as a classical pianist. After graduating from Thelma-Yelin High School for the Arts, she served in the Israel Defense Forces, and later worked as a theater composer and musical director in Israel. She won the first prize in Colors in Dance in 1992 for her music for choreography. In 1994, she moved to Boston, USA, upon receiving a scholarship from Berklee College Of Music. During her studies, she won the first prize in the yearly Professional Writing Division Concert with her first string quartet. After graduating Summa Cum Laude in 1997 (majoring in both Classical Composition and Film Scoring) she moved to Los Angeles to begin her professional career. Miss Farber was the recipient of the prestigious Academy of Television Arts and Sciences Internship in Film Scoring, as well as the Mentorship program of the Society of Composers and Lyricists, on which she currently serves as a board member. Farber's first professional work in Los Angeles was orchestrating and writing additional music for composer Shirley Walker.

A graduate of the prestigious Berklee College of Music in Film scoring and Concert composition (dual major), Sharon has been working with networks and cable broadcasters like NBC, CBS, Showtime and the WB as well as writing music for feature films. Her score for the film “When Nietzsche Wept” (Millennium Films) was commercially released and performed live in a film music concert.

Sharon was one of the few composers featured in the concert event celebrating female composers sponsored by the "Alliance for Women Film Composers” (The AWFC). The International Film Music Critics Association wrote about her piece: "Composer Sharon Farber wowed the crowd with a suite of music from three of her scores: "Children of the Fall", When Nietzsche Wept" and "The Dove Flyer"...

In the concert music world, Sharon has many national and international credits to her name, including The Los Angeles Master Chorale, Pacific Serenade Ensemble, The Israeli Chamber Orchestra, The Northwest Sinfonietta, The Bellingham Symphony, Orange County Women’s Chorale, Culver City Symphony Orchestra, The Jewish Symphony Orchestra, iPalpiti Artists International and more.

Sharon’s acclaimed concerto for cello, orchestra and narrator, “Bestemming” ("Destination" in English), based on the remarkable life story of Holocaust survivor and hero of the Dutch resistance Curt Lowens, has received many performance since its creation, recently on a 4 - city tour of the Pacific Northwest, with renowned cellist Amit Peled, conducted by Maestro Yaniv Attar. In 2019 Sharon will embark on a European tour with the piece.

Sharon’s latest commission, from the National Children Chorus, “Children of Light” premiered at Lincoln Center December 2017 and at Royce Hall in Los Angels January 2018.

Sharon is the Music Director of Temple of the Arts in Beverly Hills at the SABAN theater, where spirituality is infused with music, dance and art.

Meir Finkelstein

Meir Finkelstein (b. 1951)

Meir Finkelstein was born in Israel in 1951 the son of a chazzan. His father, the late Zvi Finkelstein accepted a cantorial position in London, England and the family emigrated in 1955. Meir showed outstanding musical abilities at an early age and along with his older brother, Aryeh was soon accompanying his father at services.

A year after his Bar Mitzvah, Meir was appointed cantor at a small synagogue in Glasgow, Scotland thereby becoming the youngest cantor in Europe. He, along with his father and brother recorded two albums of original liturgical music which were subsequently released in the USA.

At age 18, Meir took up the position of chazzan at one of London’s most prestigious congregations, Golders Green Synagogue. While serving this congregation, he also completed his musical education. Meir graduated from the Royal College of Music and received an ARCM degree in Singing, Piano and Composition. His talent was discovered a few years later by Beth Hillel Congregation in Wilmette, Il and he subsequently emigrated to the United States. Meir served as cantor of Sinai Temple in Los Angeles, USA for 18 years during which time he composed over 100 settings for the liturgy.

Meir is one of the best-documented composers of contemporary Jewish music, and his compositions are sung in synagogues throughout the world. He has collaborated with Steven Spielberg, composing music for the Visual History Foundation’s award-winning documentary, “Survivors of the Holocaust.” In 1995, Meir premiered his “Liberation” Oratorio, a large-scale and moving work written for the 50th anniversary of the liberation of the Nazi death camps, at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in Los Angeles with the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra, the Los Angeles Master Chorale, and many well-known soloists, hosted by Billy Crystal. Cantor Finkelstein is also in great demand as a producer and arranger and has collaborated on many of his colleauges' albums. He was one on the "Three Cantors" along with Alberto Mizrahi and David Propis, concertizing in the USA to sold-out audiences. Meir recently moved to Toronto with his wife Monica and their children, Noah 4, and Emily, 3. He also has two grown-up children, Nadia and Adam. Beginning in August 2002, Meir took up the post as cantor at Beth Tzedec Congregation, Toronto, the largest Conservative Synagogue in the world.

Tsippi Fleischer

Tsippi Fleischer (b. 1946)

Israeli composer Tsippi Fleischer has become well known for her innovative, creative mind. Her talents were nurtured in the cultural pluralism of the land of Israel. In her works she combines the knowledge of the indigenous cultures of her homeland with a firm foundation in Western culture. Fleischer is also known as a fine educator, and many of her students have become composers and well-known conductors. She holds academic degrees in Semitic Linguistics and Hebrew and Arabic philology, in addition to her degrees in Music Theory and Composition. She received her MA in Music Education from New York University and has completed her PhD in Musicology at Bar-Ilan University in Israel. Her many works for voices, instruments and electronic media have been performed to acclaim throughout the world. She currently teaches at Tel Aviv University.

Herbert Fromm

Herbert Fromm (1905-1995)

Herbert Fromm was one of the most prominent, most prolific, and most widely published composers of synagogue and other serious Jewish music among those German- and Austrian-Jewish musicians who found refuge from the Third Reich in the United States during the 1930s and who became associated principally with the American Reform movement—a circle that also included Isadore Freed (1900–1960), Frederick Piket (1903–1974), Julius Chajes(1910–1985), and Hugo Chaim Adler (1894–1955).

An accomplished organist and conductor as well as a composer, Fromm was born in Kitzingen, Germany, and studied at the State Academy of Music in Munich—with, among others, Paul Hindemith. After a year as conductor of the Civic Opera in Bielefeld, he held a similar post for two years at the opera in Würzburg. After 1933, when Jews were prohibited from participation in German cultural life, he was an active composer and conductor in the Frankfurt am Main section of the Jüdischer Kulturbund in Deutschland, which provided the only permitted artistic opportunities for Jewish musicians during the Nazi era until 1939. It was in that context that he began to employ Jewish themes and texts in his compositions.

Fromm immigrated to the United States in 1937. He assumed the post of organist and music director at Temple Beth Zion in Buffalo, New York, followed by a similar appointment at Temple Israel in Boston, where he remained until his retirement, in 1972. In 1940 and 1941 he worked once again with Hindemith, privately as well as during summers at Tanglewood, refining his technique and style and developing a highly individualistic approach to music for Jewish worship and music of Jewish expression—judiciously modern, yet imaginatively respectful of tradition and never on the fringe of the avant-garde. In 1945 he won the first Ernest Bloch Award for The Song of Miriam,and he was later awarded an honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters by Lesley College.

Among his large opera of liturgical and liturgically related works are several full services and numerous individual prayer settings—many of which became part of the standard repertoire in Reform synagogues—as well as Judaically based pieces geared for concert performance. Among his outstanding non-synagogal and secular works are Memorial Cantata, The Stranger, three string quartets, a violin sonata, a woodwind quartet, and many songs. Fromm also authored three books: The Key of See, a travel journal; Seven Pockets, a volume of collected writings; and On Jewish Music, from a composer’s viewpoint.

Fromm was known for his insistence on high aesthetic standards and his harsh criticism of the populist trends and the raw, mass-oriented ethnic elements that could be found increasingly in American synagogue music. Composer Samuel Adler, his lifelong friend and colleague, has recalled that it was not so much those musical elements, per se and on their own appropriate turfs, that angered Fromm as it was his view that such adulterated synagogue music “hindered the worshipper from being able to face the highest in life.” And in that context, Adler remembers that Fromm challenged himself and his work with the Hebrew admonition contained in Pirkei avot (Sayings of the Fathers), a part of the Mishna: Da lifnei mi ata omed—“know at all times before Whom you stand.”

By: Neil W. Levin

Cristiano Giuseppe Lidarti

Cristiano Giuseppe Lidarti) was an Austrian composer of Italian descent who spent his professional life teaching and performing in Italy. Most of his compositional output consists of instrumental chamber music. Beginning in 1770, the Portuguese Jewish community of Amsterdam commissioned him to compose works in Hebrew for voices with instrumental accompaniment.

Jack Gottlieb

Jack Gottlieb (1930-2011)

Jack Gottlieb contributed his considerable creative gifts to a broad spectrum of musical endeavor that spans high art, Judaically related, functional liturgical, and theatrical musical expression—as well as music criticism and scholarship of American popular idioms. He described his own music as “basically eclectic,” in the American tradition of Copland. His pungent rhythms, inventive harmonic colors, clarity, and refreshing directness bespeak a manifestly urban American influence, often also informed by Jewish musical traditions and, where applicable, by the natural sonorities and cadences of the Hebrew language.

Gottlieb grew up in New Rochelle, a suburb of New York City, and initially played the clarinet in marching bands. Throughout his youth he was conditioned by much of the music heard generally in America—especially on radio, which he recalls as very formative for him at that time: jazz, Broadway, and other emblematic American styles. During his later teen years he taught himself to play the piano, but the defining moment in his musical development and in his Jewish musical awareness came during his summer residences at the Brandeis Arts Institute, a division of the Brandeis Camp Institute in Santa Susana, California, where the music director was the esteemed and charismatic choral conductor and composer Max Helfman, one of the seminal figures in Jewish music in America. Like so many other alumni of both the camp and its more specialized arts institute, Gottlieb was permanently inspired by Helfman, whom he regarded as his “spiritual father.” The arts institute program brought together college-age students as well as established Israeli and American Jewish composers and other artists of that period in an effort to broaden the Jewish artistic horizons of young musicians. “I was still raw and not yet very musically developed” (when he entered the program), Gottlieb later recalled. But at the Brandeis Arts Institute he was introduced to new artistic possibilities inherent in modern Jewish cultural consciousness. The experience gave him lasting artistic direction.